Keeping a tiny passion alive…

An interview with Toru Hideshima, the second generation to run the hanko shop Hideshima, which has been in business for 91 years; A close look at the thoughts and feelings of a craftsman who conveys the profoundness of the Japanese language and the playfulness of the Japanese people through the appeal of hanko

Over 90 years in business; Japan’s No. 1 hanko shop

Hakozaki Shrine, one of Japan’s three major Hachiman* shrines, is located in the Higashi Ward of Fukuoka City. On a street not far from the main approach to the shrine stands the hanko shop Hideshima, which boasts the largest selection of hanko in Japan.

*Hachiman: A Shinto deity of archery and war, and thought to be the spirit of Emperor Ōjin, who reigned from approx. 270 to 310 AD.

“What’s your name?”

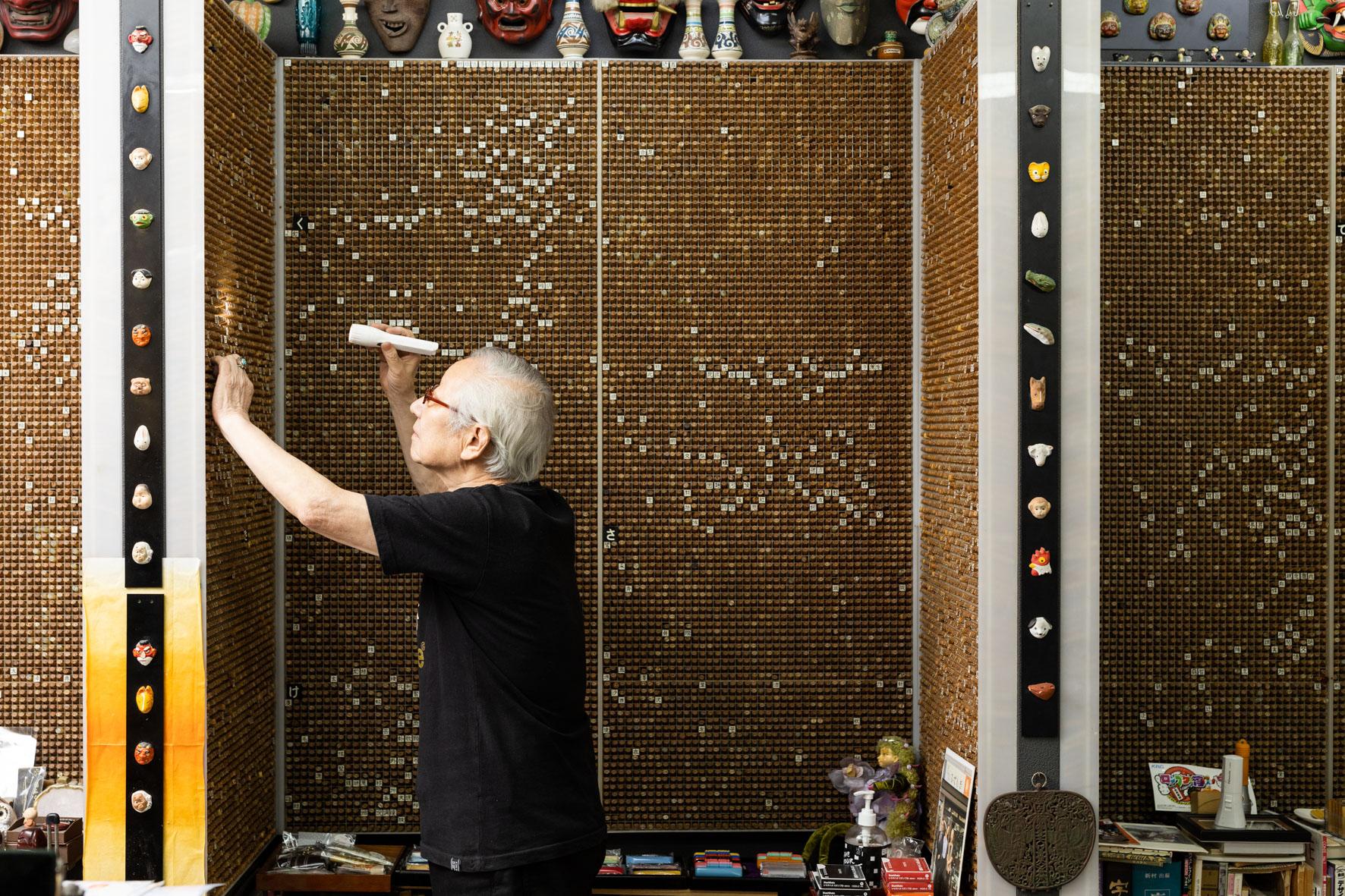

Upon replying, the shop owner picks up a well-used pen and writes my name on a convenient piece of paper. Then, he quietly moves away, picks up a flashlight, and heads over to a set of shelves built across an entire wall and high enough to nearly reach the ceiling. The shelves are tightly packed with more than 10,000 hanko, giving the impression of a giant beehive. Aided by the flashlight, the shop owner finds the hanko he’s after in just a few dozen seconds, as if he knew right where to look – whispering to himself, “Here it is.”

The shop, originally named Hideshima Inpo (Hideshima Stamp Shop), was founded in 1931 by Minoru Hideshima, the first generation of the family to run the shop. Toru Hideshima, the second generation and current owner, inherited the shop from his father at the age of twenty-five in 1972, when machine engraving was becoming commonplace. For as long as he can remember, Toru has been holding an engraving knife, picking up techniques by watching his father. He realized that he wanted to pursue the skill of hand-engraving, which he preferred over items that could be mass produced by machines. As the pillar of his business, he established himself as a manufacturer that designs hanko.

As he researched the history of hanko, a traditional Japanese culture, he quickly became enraptured by their appeal.

A creation older than the invention of paper… or even writing

The origin of hanko can be traced back to the Mesopotamian civilization that thrived around 3500 BC. More than 500 years earlier than the discovery of cuneiform, the world’s oldest writing system, cylindrical seals similar to hanko were used as protective talismans. Later, usage of these talismans expanded north across Africa and Europe, and they were introduced to China via the Silk Road. China is rich in a material called pagodite, or more colloquially known as figure stone, a soft greyish stone that is extremely easy to work. In addition, the unique culture of Chinese characters, the invention of paper, and the discovery of the raw material used in vermillion ink together led to the rapid development of hanko culture. At some point, it became common practice for powerful people to engrave their seal on all types of works of art or books as a way of ensuring their names a place in history, and some of these made their way to Japan during the Nara period (710-794).

Japan’s capital at the time was Heijo-kyo, located in present-day Nara Prefecture, and the emperor was the center of government. Within the burgeoning extravagant culture of the aristocracy, hanko were used to indicate court rankings among nobles and officials. Initially, hanko were not used for their original purpose. They were instead an accessory carried on a cord tied around the owner’s waist to symbolize wealth. Later, hanko became popular among the educated, such as Buddhist priests, writers, and artists, who began to develop hanko in a more artistic direction, including how they designed inei (the imprint of a seal left on paper, etc.).

Hanko became more mainstream in Japan from 1871, primarily driven by a system instituted by the government requiring citizens to officially register an inkan (imprint registered as a bank seal or personal seal). Under this inkan registration system, a government agency was tasked to keep records on each person’s inei along with their name, address, gender, and other information so that it could be used to provide more credible verification when entering into important contracts requiring verification of identity, such as property sales, loan acquisition, etc. The introduction of this new system liberated people in social classes who had previously been forbidden from using a surname, and this enabled them to obtain a type of hanko called a “jitsuin” used as a means of distinguishing themselves from others.

Fun names that developed from the playfulness of the Japanese people

Hideshima commented, “Surnames could all have been the same or similar. For example, we could all be named so-and-so Tanaka, so it’s interesting to see that people have subdivided into more than 100,000 different surnames over the course of time.” A number of unique surnames have developed thanks to the existence of three writing scripts unique to the Japanese language: Kanji (logograms introduced from China with each written character representing a word or concept), hiragana (phonetic syllabary written in a cursive style), and katakana (phonetic syllabary written in a more angular style). Japanese people have enjoyed the process of creating new words and phrases by combining these scripts and playing with sounds and connotations. It is also speculated that people may have been influenced by the fact that poetry forms such as haiku, tanka, senryu, etc. and other ways of expressing the beauty and playfulness of words had already taken root as a part of the culture in Japan.

Surnames have evolved from numerous plays on words, and it’s exciting to ponder their origins. In addition to names derived from Japanese place names and occupations, many unusual names, such as 辺銀 (Penguin) and 猫屋敷 (Nekoyashiki), have also appeared.

For some people, a misprint on one of many official application forms or a misreading by a government official in charge have led to the mistake being registered as their official surname. Also, people with rare surnames typically have to order custom-made hanko because most hanko shops don’t carry their name.

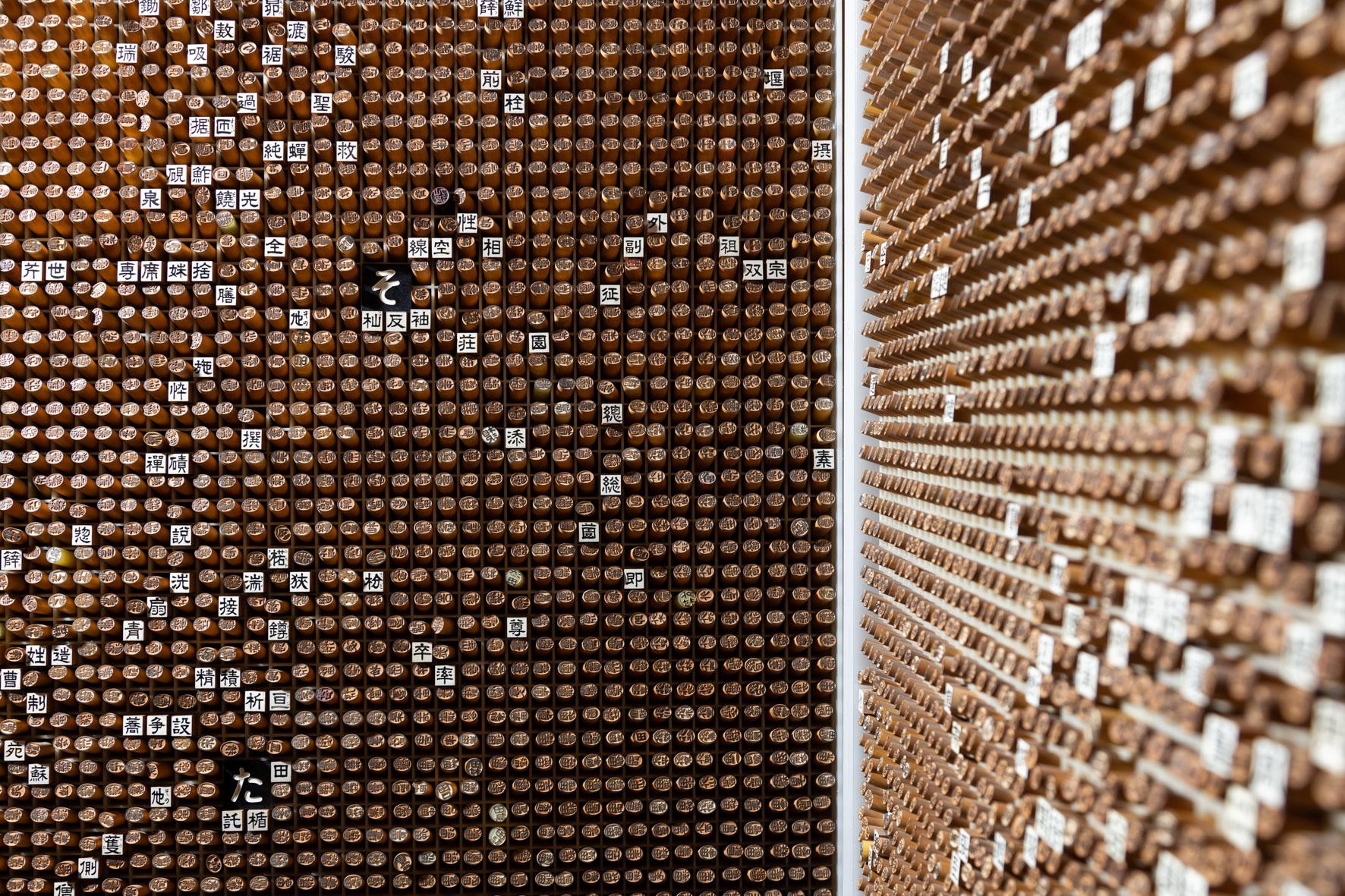

Hideshima became interested in these sorts of niche surnames, and about 40 years ago, he began to offer hanko in a wider range of surnames.

“I don’t want to make any customer wait…”

Devoting himself to this purpose, he began scouring every day through not only dictionaries but also newspapers, television shows, books, manga, telephone directories, and any other type of media he could get his hands on in search of surnames that he had never seen before. He kept a pen and paper with him at all times. Before he knew it, it had become routine for him to ask and record the surnames of anyone who visited his shop. Whenever he encountered a surname that seemed too bizarre, he would contact the government office in charge to confirm that it actually existed. If it did, he would create a hanko for it and add it as one of his products – even though no one had placed an order for one.

Recently, he has made numerous media appearances as a “surname researcher.” Hideshima’s shop is a truly fantastical and peculiar spot, visited on a daily basis by bearers of rare names from across Japan.

The appeal of hand-engraved hanko of captivating craftsmanship

If all you want is to make a hanko with your surname on it, then you could do it with a machine, and Hideshima knows this better than anyone. That’s precisely why he maintains his pride as a designer who creates hanko by tracing back to the roots of each name and surname.

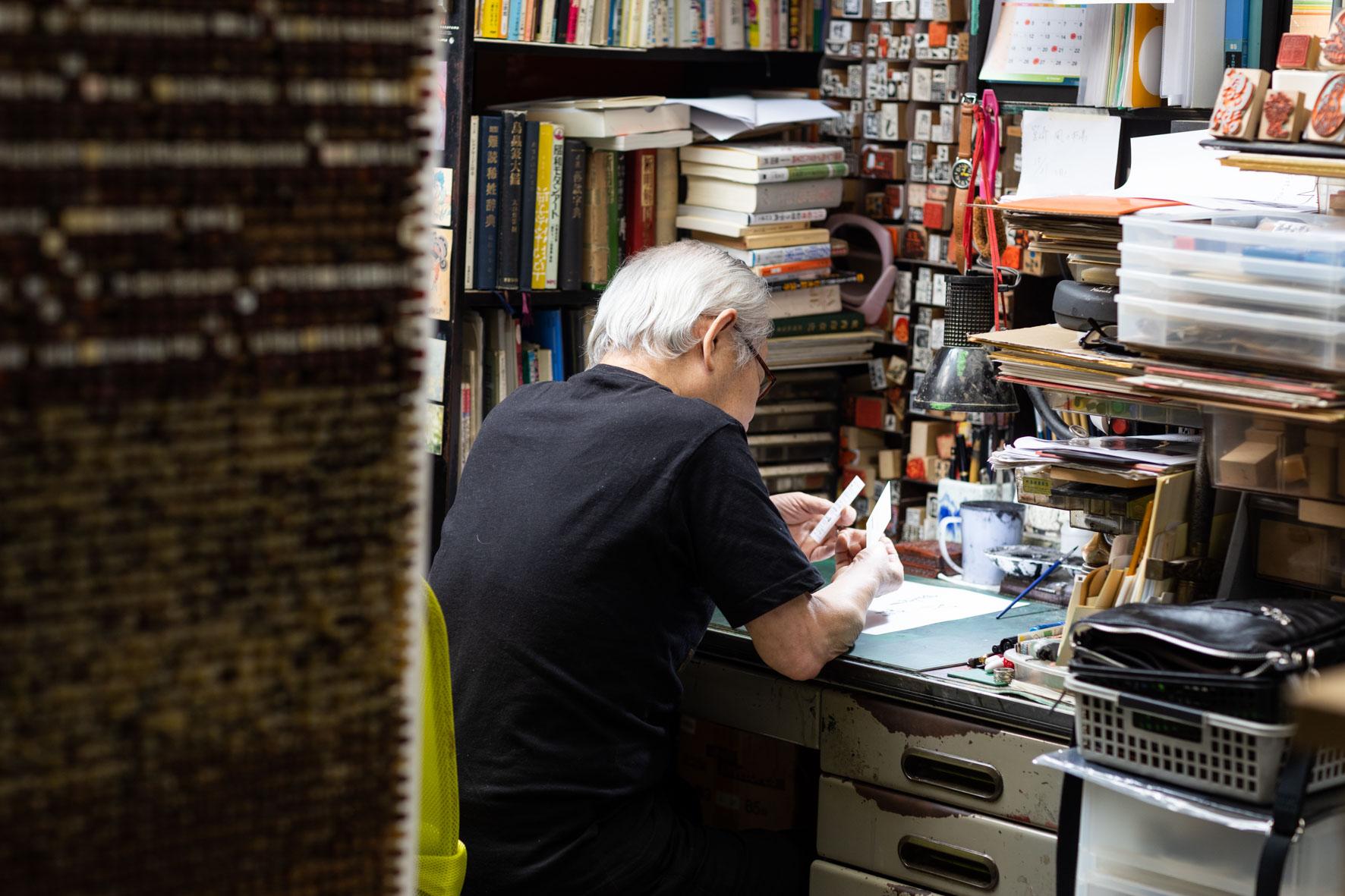

The first step in the creation process is to make rough drafts of the client’s name using ink and a brush. Once he has finalized the typeface, he draws a simple template on the end of the hanko and picks up a steel engraving knife that he personally forged. The basic motions of engraving are pushing, pulling, and tapping, and the engraver can begin from any point on the template. Some places are forcefully engraved as though applying one’s entire weight behind the very tip of the blade, and other places are delicately engraved using force subtle enough to divide a single millimeter into 100 equal parts. If Hideshima makes even a single mistake, he starts over from the very beginning. As he proceeds, he engraves as though breathing life and soul into the hanko. From his breathing alone, an air of concentration fills the workshop.

After finishing the engraving process, he inks the hanko using a vermillion ink pad and tests it on a piece of paper. According to Hideshima, it takes at least two years of practice before an engraver’s inei begin to stand out attractively. After a series of fine adjustments, the engraving knife is hot as he approaches completion of a satisfying engraving, and he suddenly relaxes his arms.

Hideshima has been making hanko for half a century, and he says that, now at the age of 74, his hands are numb for several hours after the monumental task of engraving a single hanko.

Peering closely at the surface of a completed hanko, amidst the elaborateness, you can sense a character and quality in the engraving that is only achievable by hand. Hideshima’s hanko are truly one-of-a-kind works of art that reflect the personality of the client. Due to the high quality of his designs, he has handled more than 1,000 requests, from numerous calligraphers, artists, sumo wrestlers, and other celebrities, as well as from foreign dignitaries.

“Rather than forcibly creating a kanji name by applying a character with the same pronunciation, I always design names using auspicious kanji characters as well as words or phrases that match the overall atmosphere and impression of the client – because the charm of a hankolies in the words and characters themselves.”

From this comment, I could sense Hideshima’s extraordinary devotion to conveying the appeal of the Japanese language through his creation of hand-engraved hanko.

Continuing to engrave Japan’s unique hanko culture

In recent years, as a way to prevent the spread of Covid-19 infections and in recognition of the Digital Age, Japan has been abolishing the need for hanko in administrative procedures and on internal documents (i.e., going hanko-less). When asked for his opinion on the declining demand for hanko in light of these current circumstances, Hideshima calmly replied, “The practical hanko used administratively will likely disappear in about 15 years.” He added that, in the future, the demand will be for hanko that feature the artistic style that once flourished in Japan and that are more in line with their originally intended meaning.

Hideshima said, “Even if hanko change in form, they will remain as an aspect of Japanese culture, and we need to preserve them. I want to continue making individual hanko that people become fond of and want to use forever.” The continued existence of hanko as a Japanese tradition is backed by the powerful sentiments of craftsmen who continue to engrave them with dedication to preserve the culture and their well-hone, unique skills.

*Supplementary explanations

Inkan: An imprint registered as a bank seal or personal seal.

Inei: The imprint of a seal left on paper, etc.

Hanko: The stamp itself; the article upon which characters, etc. are engraved. The official term is insho.

Profile

Hideshima Toru/Hanko Designer

Born in Fukuoka City, Fukuoka Prefecture. The second generation to run the hanko shop Hideshima. As a hanko designer, single-handedly performs every step of the creation process from design to engraving.

Hanko Shop Hideshima (Hideshima Chokoku Kogyo Co., Ltd.)

1-36-38 Hakozaki, Higashi Ward, Fukuoka City

+81-92-651-3085

Interview and text:Natsuki Shinmoto(Chikara)

Translation:Aaron Schwarz

Photography:Kazuhiro Kaku

Project Direction:Chikara

![[2026] Strawberry Picking Spots in Fukuoka-1](https://www.crossroadfukuoka.jp/storage/special_features/49/responsive_images/9ZHgrqvQdpH8tM4IRF54DXu0aPBF3YGGkj5WOTGc__1673_1115.jpg)

![[2026 Edition] Filled with blessings! The ultimate Fukuoka power spots to bring you happiness.-1](https://www.crossroadfukuoka.jp/storage/special_features/320/responsive_images/6SsCvBDXBhlZoAGUgarTOpZpEaEwsIqsWzSxW8cw__1289_856.png)