Sugar Road: tracing the history of famous Fukuoka sweets that developed along the Nagasaki Kaido

Japan, a powerhouse of confectionery! Japanese sweets date back to the Edo Period (17th to the 19th century). The Nagasaki Kaido, the road connecting Nagasaki, prosperous foreign trading port and Kokura in Kitakyushu City, Fukuoka Prefecture was a route that carried tremendous volumes of sugar, and it also ushered in the culture of sweet-making. Hence, it came to be called “Sugar Road” and unique food cultures incorporating the use of sugar developed in communities along the route.

In this special edition, we delve into the history of the Sugar Road and showcase a number of renowned traditional sweets of Fukuoka Prefecture.

A new, sugar-centric food culture begins along the Nagasaki Kaido

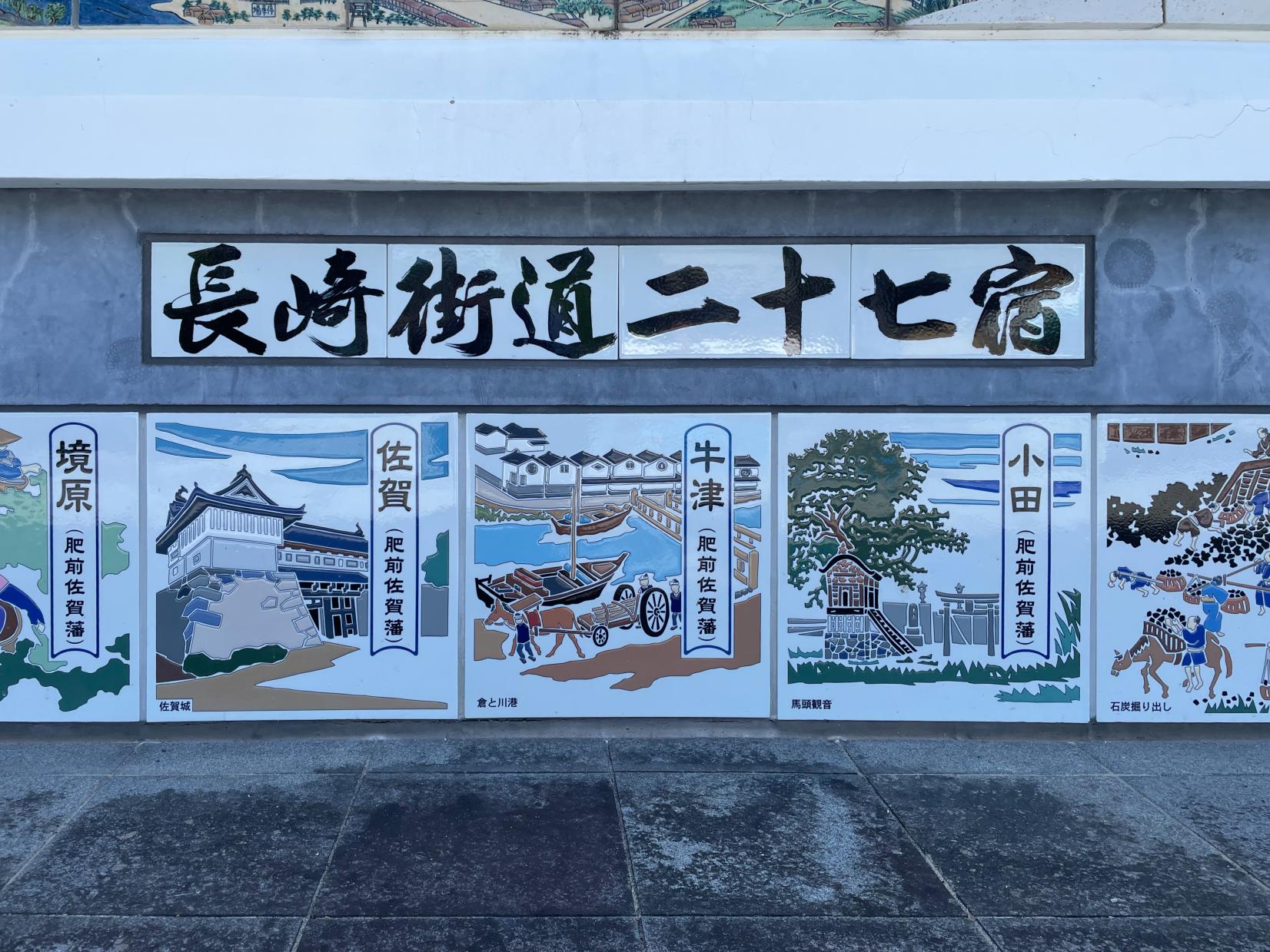

While Japan may have imposed the sakoku policy during the Edo period, it did not mean the nation was hermetically sealed from the world. Throughout the sakoku era, the Nagasaki Kaido was the one road connecting Japan to China and the West.

It is 228km in length. Between its starting point in Kokura, Kitakyushu and Nagasaki, the only port in Japan that permitted international trade under the direct control of the Shogunate, were 25 staging-post towns (towns that prospered as transportation hubs).

Nagasaki Kaido was a vibrant thoroughfare travelled by all sorts of people from the daimyo lords from all over Kyushu on their way to or from Edo under the sankin-kotai “alternative attendance” system, samurai on their way to perform security duties in Nagasaki and Dutch East India Company chief traders visiting the Edo shogunate, as well as everyday merchants and artisans plying the route on foot. It also prospered as an artery for imported goods and new technologies and culture from other countries to the rest of Japan.

The sugar flowing from Nagasaki to the rest of Japan found its way into the communities along the road together with sweet-making techniques, giving rise to a blooming patchwork of unique confectionery cultures.

Column

Chikuzen-mushuku (“the six staging-post towns of Chikuzen”) and the Hiyamizu Pass

At that time, there were six staging-post towns in Fukuoka Prefecture bustling with travelers and goods. These were Kurosaki and Koyanose in what is now Kitakyushu City, Iizuka and Uchino in Iizuka City, and Yamae and Haruda in Chikushino City. As a group these were called “the six staging-post towns of Chikuzen”.

It all began in 1612 when the first lord of the Fukuoka domain, Kuroda Nagamasa, ordered construction of the Nagasaki Kaido over the Hiyamizu Pass to ease the mountainous route between Uchino and Yamae. From 1635, when the Tokugawa Shogunate imposed the sankin-kotai system, this became the route for lords traveling to Edo and the development of the staging-post towns began in earnest.

From sugar as a rarity to sugar as a bulk import

Sugar first reached Japan during the Nara period (8th century). It was not used as a food at the time but rather, as a medicine in very small quantities.

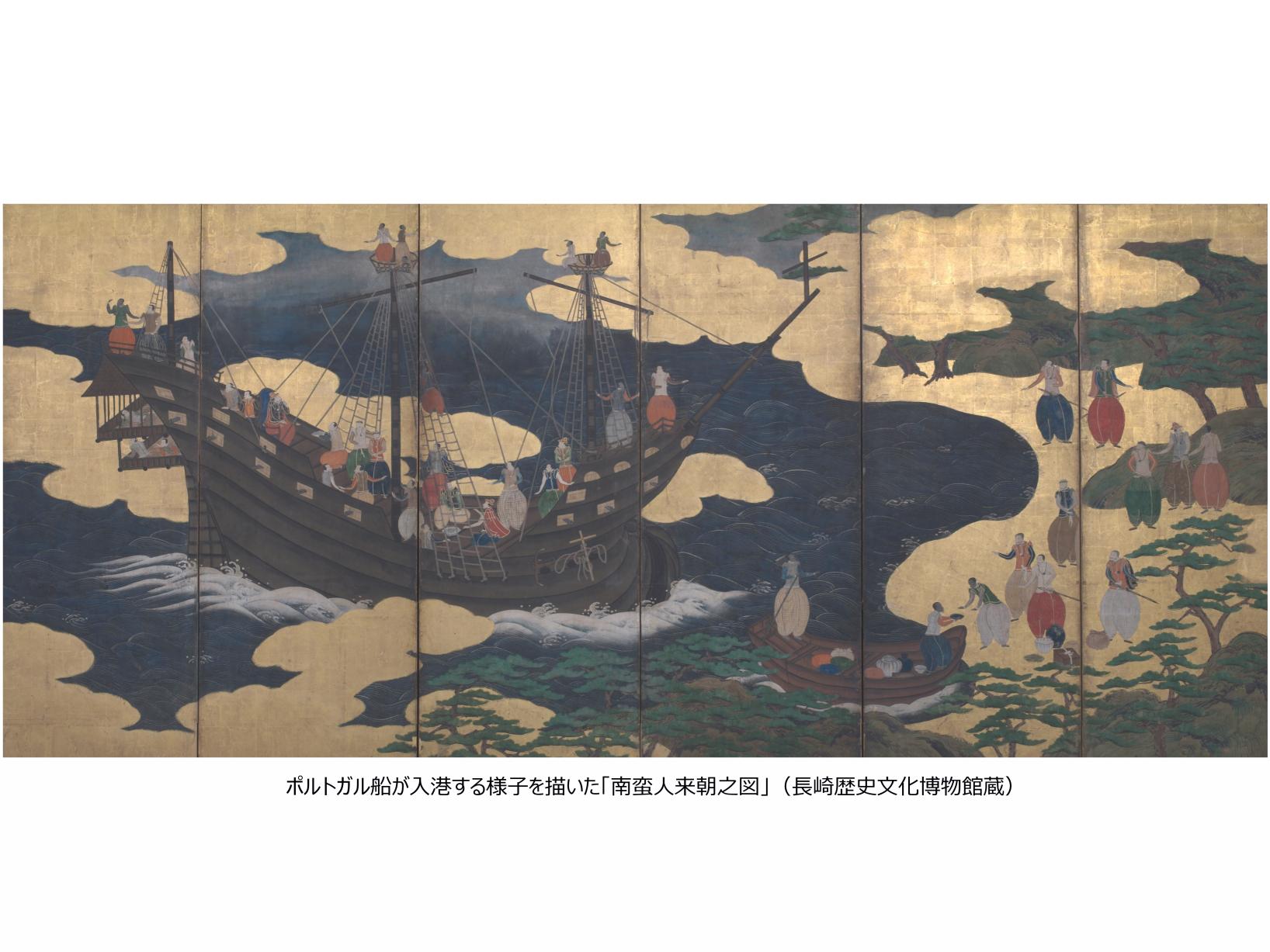

It only began to be imported in bulk in the late 16th century in trade with the Portugese. Luís Fróis, a priest from Portugal, traveled to Kyoto to obtain permission for a Christian mission, where it is recorded that he presented Oda Nobunaga with kompeito candy in a glass jar.

In the Edo period, Portugese ships were banned from entering Japanese ports under the sakoku policy, and Dutch and Chinese ships carrying goods from Asia and Europe started to arrive instead. One of their key products was sugar, of which bulk importation began in the 18th century.

Westerners Arrive in Japan (1596 –1615) / Screens of the Portogueses Arriving in Japan

Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture

Nagasaki overflows with sugar

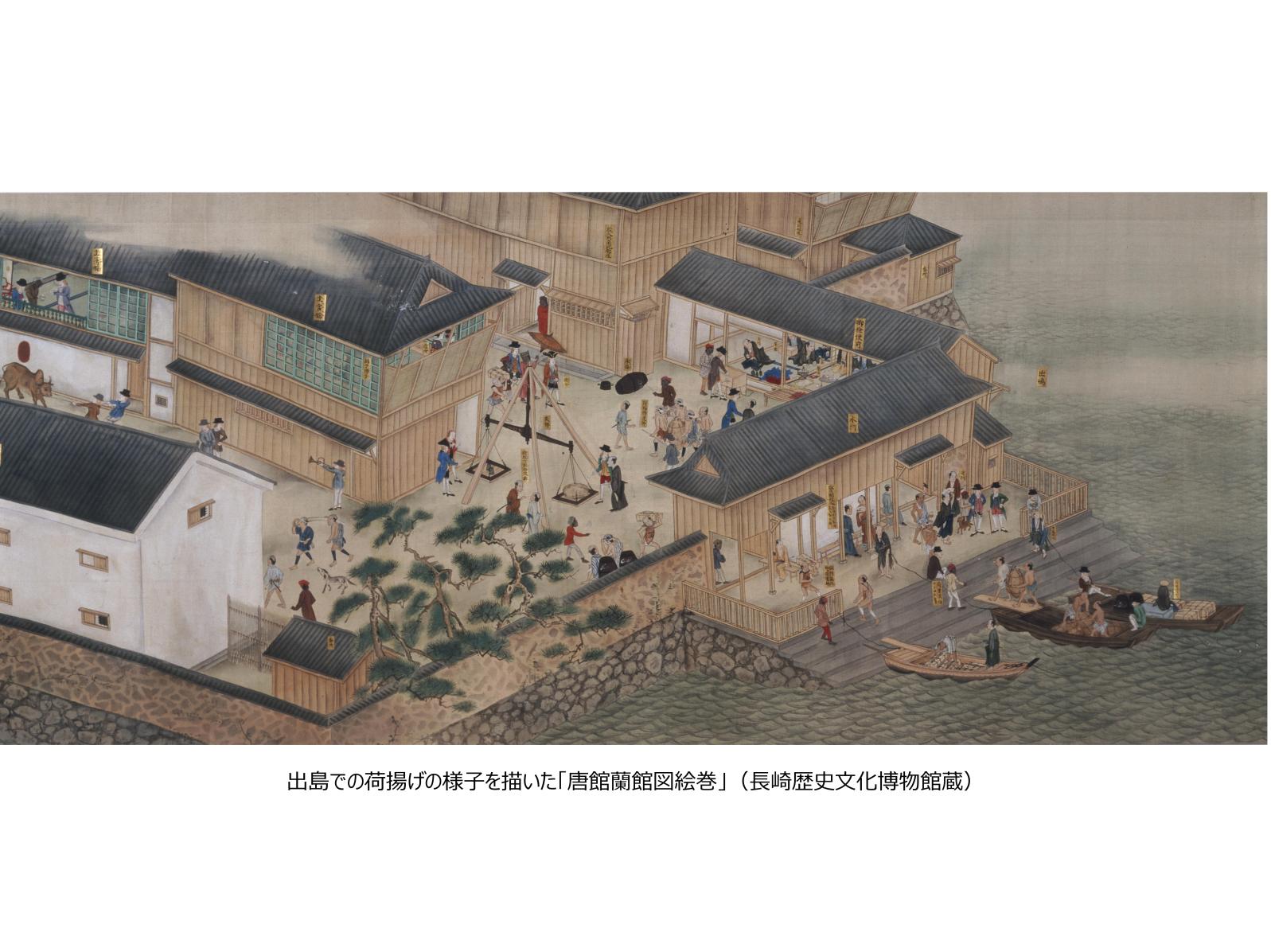

Sugar imported to Nagasaki by foreign vessels, particularly Dutch and Chinese ships, was first landed on Dejima island or elsewhere in the port. It would then be bought wholesale by Nagasaki Kaisho (clearinghouse), the Tokugawa shogunate agency that oversaw trade in the port. Sugar was then auctioned off to Japanese merchants. The majority of those merchants carried their sugar onward to Osaka by ship, but sugar found its way around Nagasaki in all sorts of ways outside of the official trade routes.

Views of the Chinese and Dutch Factories in Nagasaki

Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture

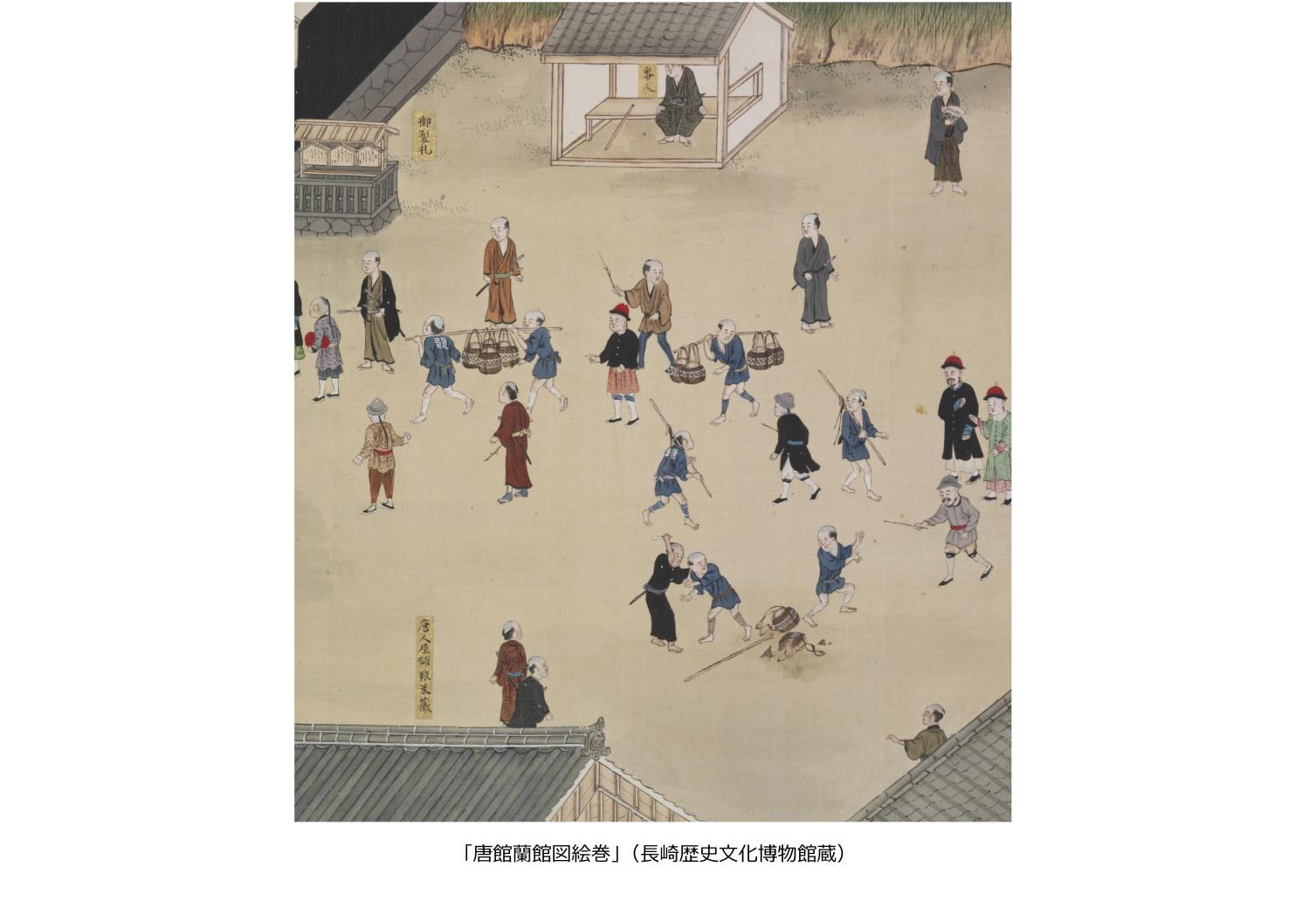

Views of the Chinese and Dutch Factories in Nagasaki

Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture

For example, Dutch trading post officials and Chinese merchants would gift sugar to the working girls of the Maruyama geisha district. Day laborers at the port were also given a ration of sugar in advance to prevent them from secretly siphoning off sugar while they worked. Even more sugar was donated by Chinese ships to Chinese-style temples in Nagasaki such as Kofukuji and Fukusaiji.

It is likely that the volume of sugar traded around Nagasaki outside of the official channels was 5-10% of the total imported volume.

Zooming into one area of the picture scroll, it shows dock workers near a dropped container with sugar spilt from it

Direct sugar transport route created by Fukuoka domain

The Edo period was also the time when sugar reached Fukuoka Prefecture. Then, both Fukuoka and Saga domains were tasked by the Tokugawa shogunate with the security of Nagasaki. Each domain would dispatch 2,000 samurai warriors every other year to Nagasaki. Procurement of food and other materials for the contingent was costly and the Nagasaki security requirement posed a heavy fiscal burden for the domains.

In order to reduce the cost, Fukuoka domain established a goods storage and sales facility in Nagasaki. More trusted merchants were eventually allowed to run wholesale businesses, and an exclusive sugar transportation route for direct importation of sugar to Fukuoka was created to bypass the existing Osaka route. Saga domain did much the same, which explains why the two domains of northern Kyushu have been so heavily laden with sugar since the 18th century.

Who brought in the food culture of using sugar?

Trade with Portugal was banned in 1639 and all Portuguese were expelled from Japan. Yet, the sweets they brought to Japan – the namban-gashi such as castella cake, bolo and confeito – went on to become highly popular snacks redolent of exotic foreign countries. The Chinese residents of Nagasaki are thought to have played a key role in preserving the methods and skills required to make such confections until they were restricted to the gated Tojin Yashiki (“Chinatown”) district in 1689.

After this, the number of candy-makers and candy stores increased in Nagasaki. Around 1720, it seems that namban-gashi were being sold all over town as souvenirs of Nagasaki.

In this environment, the scholars, doctors, walking merchants and artisans from across Japan who came to Nagasaki to learn about Western science, technology and medicine from the Dutch became attached to the use of sugar in foods. They in turn brought the confectionery techniques developed in Nagasaki to the rest of Japan via the Nagasaki Kaido.

A “Second Sugar Road” in Fukuoka Prefecture

Toward the end of the Edo period, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce was signed between Japan and the United States, opening ports all around Japan to the world, starting with Yokohama. As a result, the relative status of Nagasaki as a trading port would steadily decline. What is more, railways started operation in Kyushu in 1889. The prosperity of the Nagasaki Kaido dwindled.

However, the Sugar Road never closed. In 1904, a sugar refinery was established in Moji, Kitakyushu City fed by sugar imported from Taiwan, giving birth to the “second Sugar Road” in northern Kyushu.

At the same time, investment was flowing into the coalmines of the Chikuho region from the industrial conglomerates Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo and Furukawa. Once the Imperial Yahata Steel Works were established, Fukuoka Prefecture developed as the leading edge of modern industrialization in Japan based on mining and steel production. For the laborers working in the coalmines and steelworks, sugary sweets were treasured as a snack that could quickly boost energy levels.

The railway, developed to transport coal, was also tasked with carrying sugar and beans, the ingredients of confectionery. Trains loaded with these ingredients of yokan (sweet jelly) were certainly a fitting sight on the modern Sugar Road.

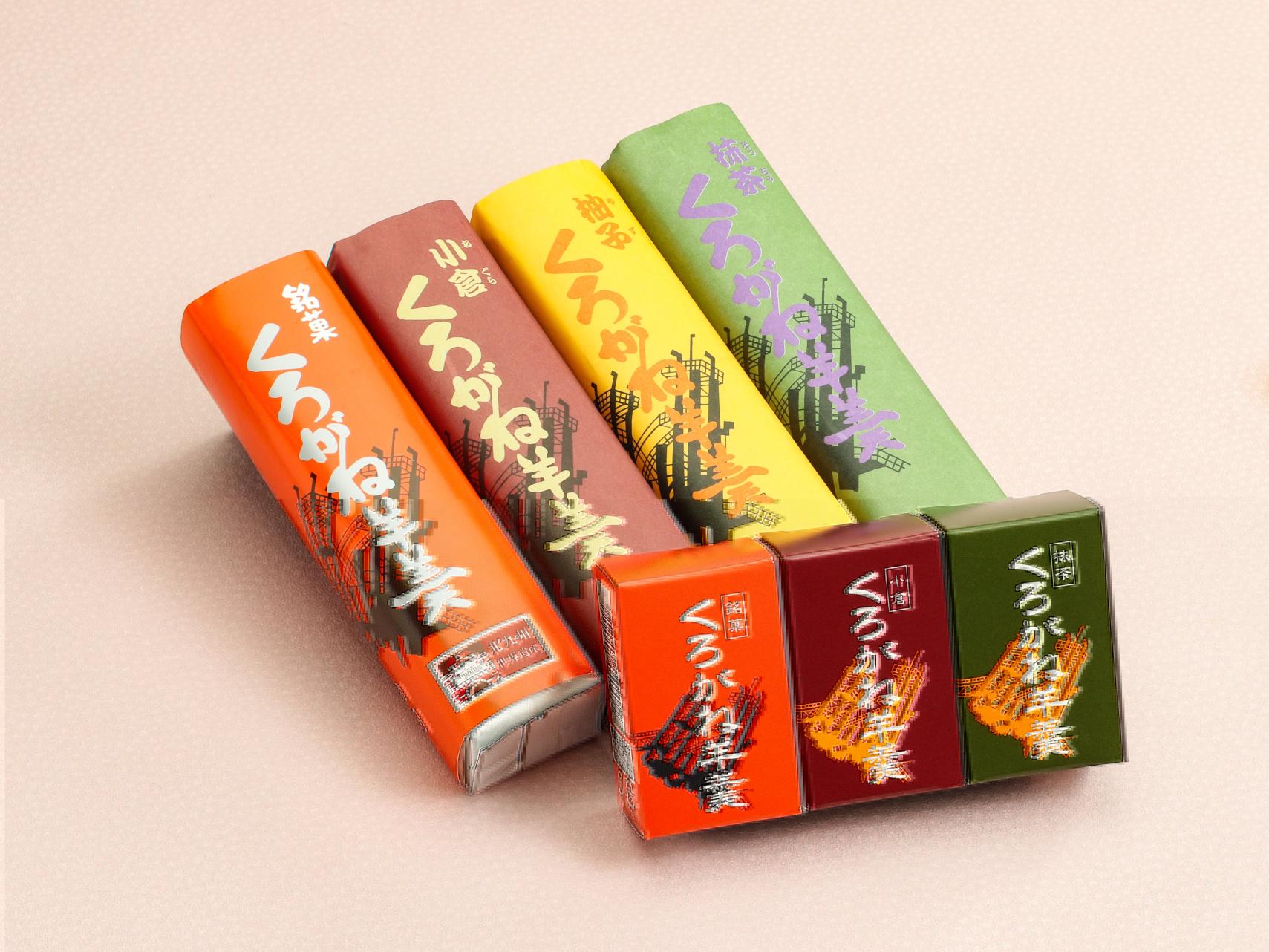

The famous candy of Iizuka, the “Chikuho coal capital”

Edo period Fukuoka Prefecture was the location of a thriving malt syrup (bakuga-ame) sweetener industry, which was made by saccharifying glutinous rice with malt enzymes. Malt syrup production continued even after the arrival of sato-ame sugar candy that used sugar as its main ingredient. But with modernization, the prosperity of the coal industry changed things. People were drawn to castella manju (buns) made of a wheat flour and egg-based dough, baked with a white bean paste filling of bean and sugar. Castella buns, a product of namban-gashi influence, were a prized gift and together with the development of coal mining, created a new sweets culture in the Chikuho region.

Iizuka Honmachi Shopping Street Karakuri (performing) Clock

-

Hiyoko Sweets

Hiyoko Honami FactoryAt a time when all manju buns were offered in the form of either a circle or a square, the cute baby-chick shape of the Hiyoko Sweet was a hit. The product was launched in Tokyo in time for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. “Tokyo Hiyoko” was sold at Tokyo Station and other venues and became widely known as a souvenir of Tokyo.

-

Chidori Manju

A baked manju with a thin castella crust and white bean paste filling, imprinted with the Chidori stamp. Among the miners, such sweet foods were a valuable way of boosting energy and were also popular as souvenirs to take back to the family elsewhere in Japan. Chidori Manju is said to have been a favorite of famous local mine owner Ito Denemon.

-

Yamada Manju

A baked castella manju consisting of soft, springy bun and melt-in-the-mouth sweet yolk bean paste. Shaped to resemble Bota-yama (the hillls that are a symbol of the Chikuho coalfield made from waste material removed during mining) and with good plain flavor, these creations have been loved for generations.

-

Black diamond

Coal, the driving force of modern Japan, was so important it was called kuroi daiya (black diamond). The Kuro Daiya Yokan from Kameya Nobunaga is distinguished by its lumpy black look, just like the coal that brought so much prosperity to the Chikuho region. This soul food of a coal mining town is much loved to this day.

Column

Iizuka and Uchino, where post-town heritage is retained

Iizuka City is home to two of the “Chikuzen six staging-post towns” on the Nagasaki Kaido.

One is Iizuka at the junction of the Onga River and the Nagasaki Kaido, which was a lively interchange of travelers and goods. The other, Uchino, was the closest post-town to Hiyamizu Pass, the most difficult point on the Nagasaki Kaido. This town prospered as a place to stay the night before crossing the mountain pass.

Both retain features of their history as staging posts, so why not take some time for a stroll guided by signposts and stone tablets?

Northern Kyushu really has enjoyed sweet flavors since the Edo period

In the northern Kyushu region, the namban-gashi from Nagasaki only began to be made broadly after the start of the modern era.

However, if we look at the record from the Edo period, the tooth cavity rate of people in Kokura was 26.9%, worse than double that of Tokyo (Edo) residents at 11.7%. This tells us that sugar may have been used on a daily basis in Kokura at the time.

When the Imperial Yahata Steel Works were established in 1901, there was high demand for sugar candy from workers fatigued by heavy labor. From this demand emerged the numerous unique and well-known confections of northern Kyushu.

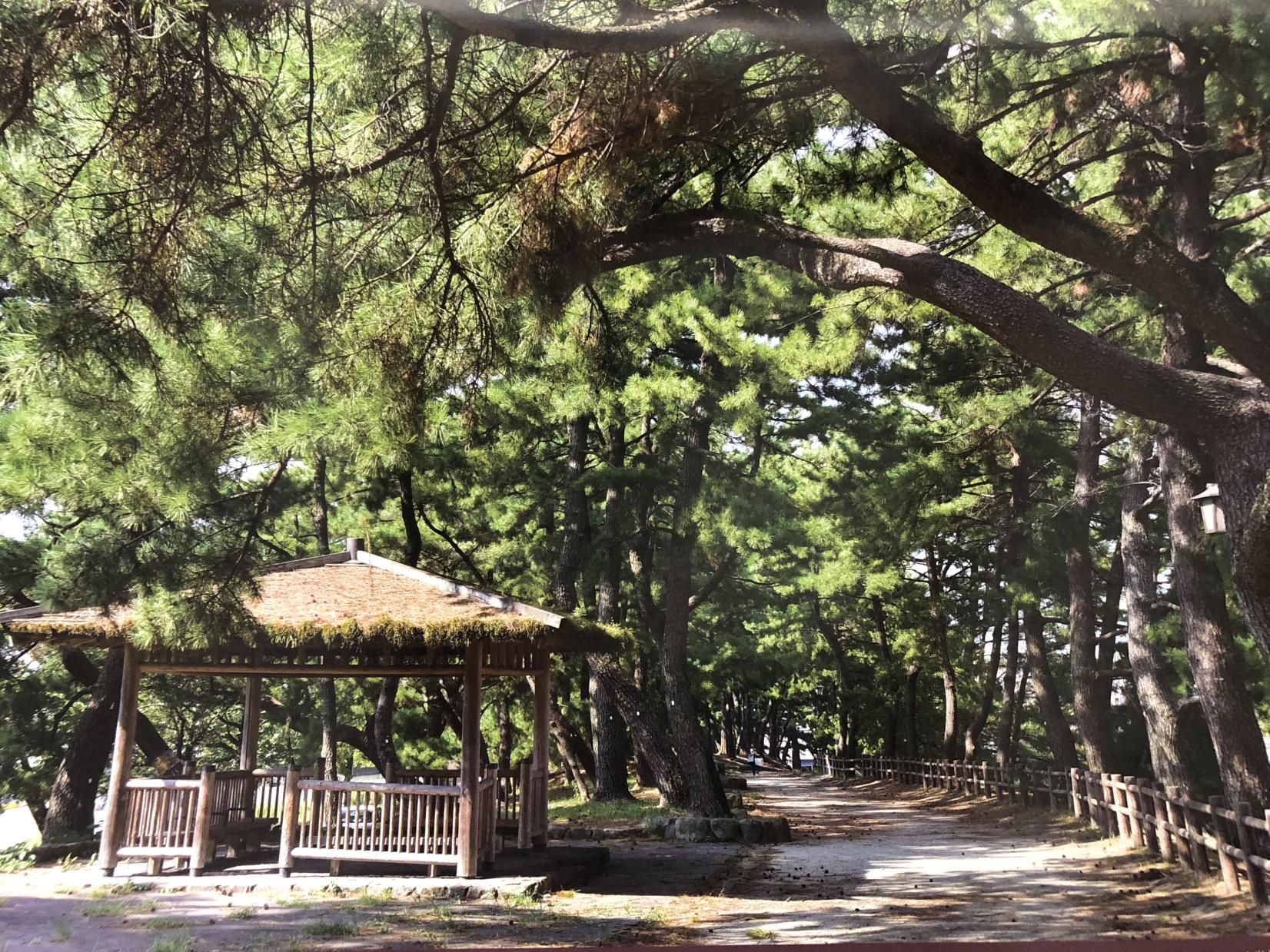

Avenue lined with pine trees reminiscent of the old road from Kurosaki to Koyanose

-

Kuri Manju

Kuri (chestnut) Manju consists of a bun made in the style learnt through foreign trade during the Edo period and a filling of chestnut and bean paste. This is the signature product of Kogetsudo, Kokura’s oldest sweet shop. Thanks to the use of dried chestnut, called “kachiguri,” the product became known for bringing good fortune (kachi also means “win”).

-

Kogiku Manju

A manju bun whose name derives from the fact they used to be sold in picturesque “Kiku no Nagahama” (the shoreline from Kokura to Moji), which is depicted on the packaging. The bun part of these bite-size manju is made from rice flour and ground yam, and is filled with white and red bean paste. After gaining a reputation through word of mouth among travelers on the road, these became a Kokura souvenir.

-

Kurogane Yokan

This “black steel” sweet jelly was developed and sold by Yahata Steel Works as a nutritional supplement for steelworkers. It is made from caster sugar to enhance its sweetness. Each yokan comes in a practical small pack designed to fit a chest pocket of the factory uniform. Prized by laborers as a source of calories.

-

Konpeito

Konpeito is among the most famous of all namban-gashi. The version introduced from Portugal, confeito, consisted of poppy and sesame seeds bound in hardened sugar syrup. In Japan, these were replaced by coarse grains of sugar, becoming konpeito made solely from sugar. Today, Irie Seika in Yahatanishi Ward, Kitakyushu is the last remaining maker of the candy using traditional methods.

Column

Kojusan Fukuju-ji Temple’s contribution to the development of confectionery culture in Kokura

At the beginning of the Edo period, the lord of the Kokura domain, Ogasawara Tadazane, invited a high priest from China and built a magnificent temple, Kojusan Fukuju-ji, to honor his ancestors.

Confectioners who served the domain would come and go from the temple, making offerings of manju buns and other sweets. As the temple had not just a religious role but was also a cultural hub, it surely had a significant influence on the development of the confectionery culture.

Try the famous sweets of Fukuoka that were born of the Sugar Road

More than 400 years have passed since sugar gained a true foothold in Japan. The sugar-based food culture that took root via the Sugar Road developed to reflect the characteristics of each region through people's ideas and ingenuity, and is still cherished and passed down to this day.

If you visit the communities along the Nagasaki Kaido, you too can get a close-up view of the sweet makers’ skills or even try making your own sweets. As you savor the famous confectionery presented here, do not forget the rich history of sweets made possible by the Sugar Road.

Tokiwa Bridge, the starting point of the Nagasaki Kaido and the terminus of the Sugar Road

Column

Nagasaki Kaido/Sugar Road, source of our sugar culture, recognized as a Japan Heritage

Nagasaki Kaido/Sugar Road, source of our sugar culture, was recognized as a Japan Heritage in 2020 based on a range of factors including its role in the historic spread of sugar and confectionery culture, the traditional techniques passed down in its communities and scenic value of each, and the local revitalization initiatives harnessing these attributes.

Since the registration of heritage status, visitor numbers to the Nagasaki Kaido have surged with interest in the history of sugar and to enjoy the traditional sweets along the way. Local governments along the route are also working more closely together as they seek to further boost their communities.

Reference

Japan Heritage

The Sugar Culture of Nagasaki Kaido: the Sugar Road Guidebook

Produced and published by Sugar Road Liaison Council

![[2026] Strawberry Picking Spots in Fukuoka-1](https://www.crossroadfukuoka.jp/storage/special_features/49/responsive_images/9ZHgrqvQdpH8tM4IRF54DXu0aPBF3YGGkj5WOTGc__1673_1115.jpg)

![[2026 Edition] Filled with blessings! The ultimate Fukuoka power spots to bring you happiness.-1](https://www.crossroadfukuoka.jp/storage/special_features/320/responsive_images/6SsCvBDXBhlZoAGUgarTOpZpEaEwsIqsWzSxW8cw__1289_856.png)